What Actually Matters When Eating Whole Grains

Whole grains are often marketed as a nutritional shortcut to better health. Walk through any grocery store and you’ll see “whole grain” stamped on breads, cereals, crackers, and pastas, all implying a healthier choice by default. But the reality is more nuanced. While whole grains can support metabolic health, digestion, and long-term disease prevention, not all whole grains behave the same way in the body. How a grain is processed, prepared, timed, and paired with other foods often matters more than the label itself.

Eating whole grains wisely requires understanding how they affect blood sugar, mineral absorption, gut health, and energy regulation. For some people, whole grains are stabilizing and nourishing. For others, they can quietly contribute to fatigue, cravings, or digestive stress. The difference lies in context, not marketing.

Why Whole Grains Matter (When Chosen Well)

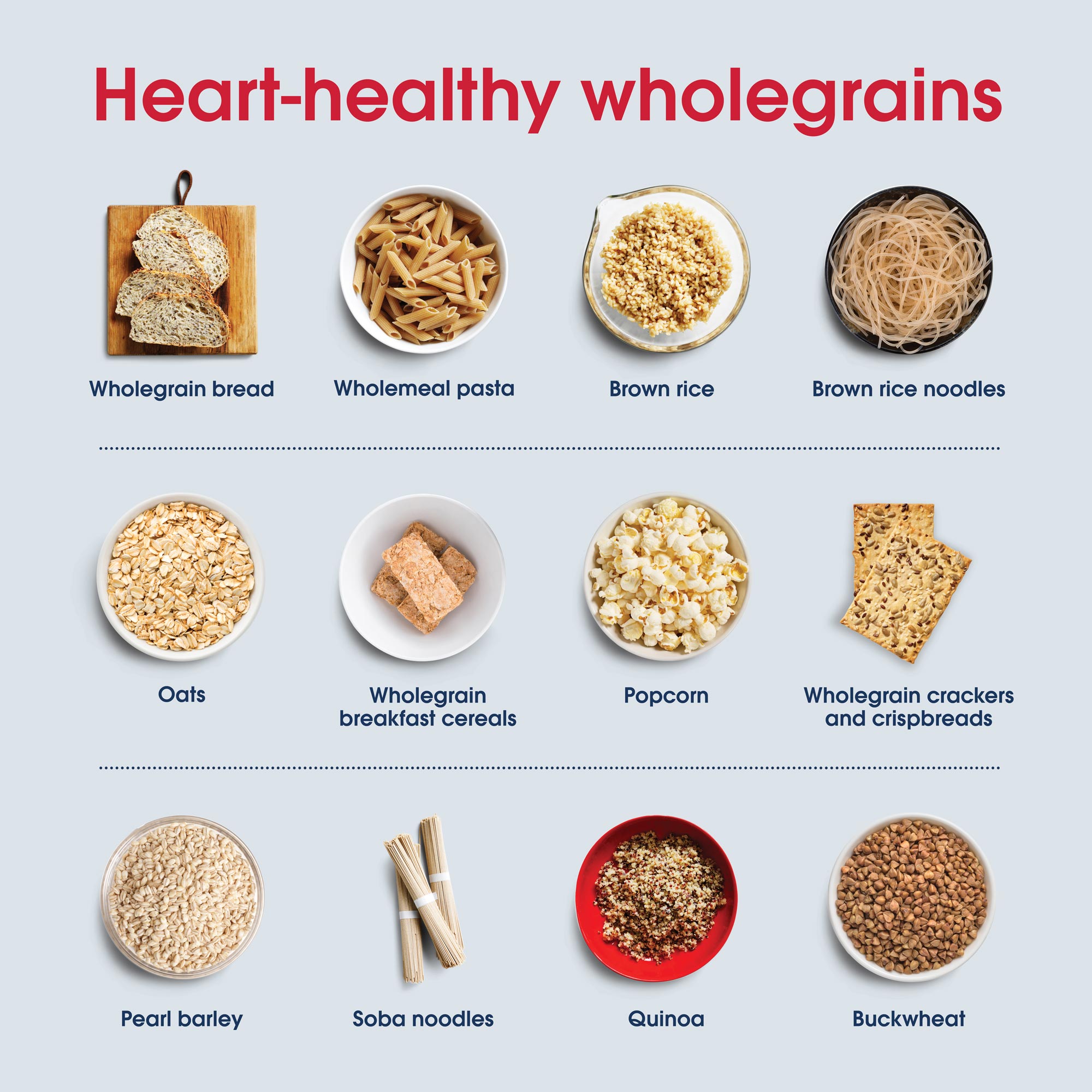

Whole grains contain all three parts of the grain kernel: the bran, germ, and endosperm. This structure provides fiber, B vitamins, minerals like magnesium and zinc, and a range of phytonutrients. Epidemiological studies consistently associate whole grain intake with lower risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and all-cause mortality when compared to refined grains (Aune et al., 2016).

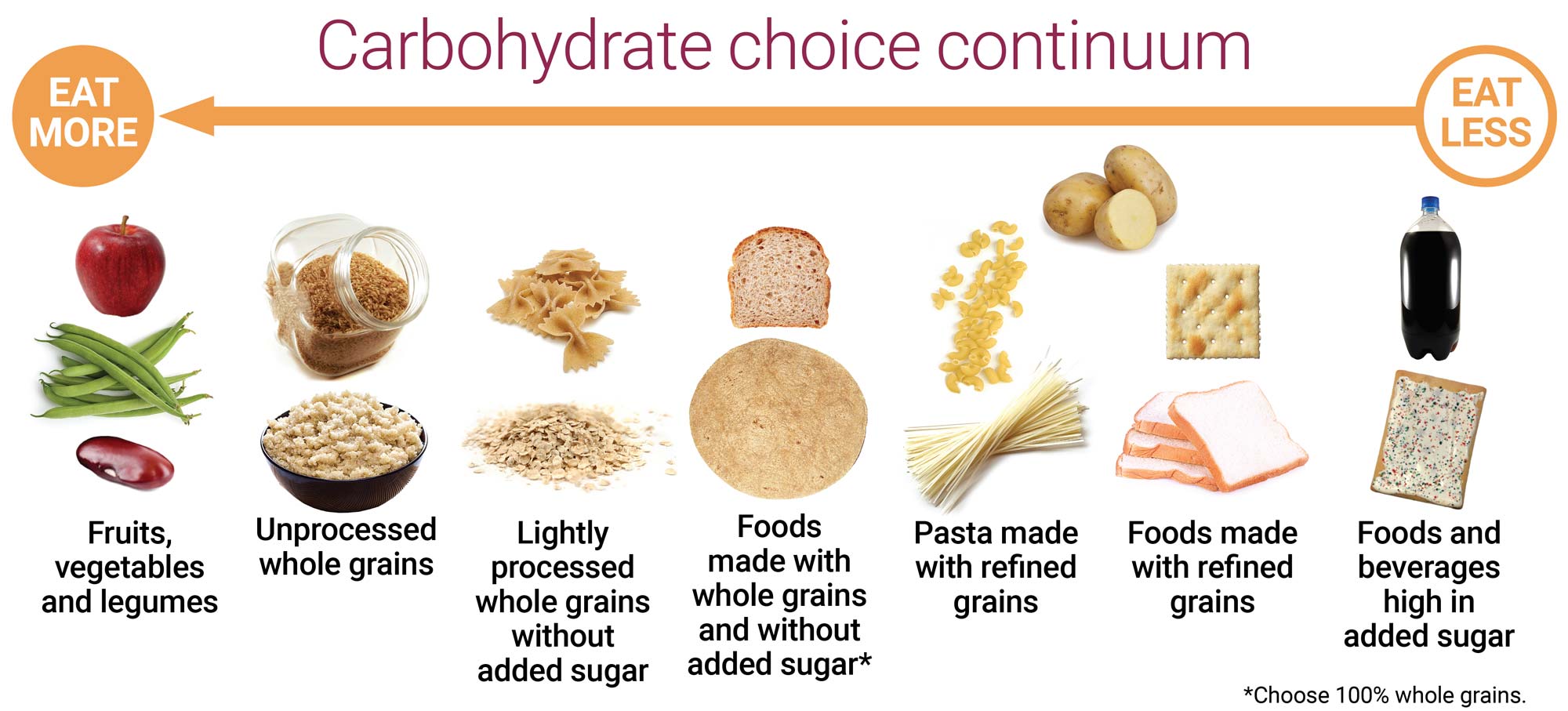

However, these benefits are strongest when whole grains are minimally processed and consumed as part of a balanced diet. Whole grains slow digestion, moderate glucose absorption, and increase satiety, but only when their physical structure remains largely intact. Once grains are finely milled into flour, extruded, or sweetened, they begin to behave much more like refined carbohydrates in the body, despite still qualifying for a “whole grain” label.

This is why two foods with identical labels can have dramatically different metabolic effects.

Processing Changes Everything

One of the most overlooked factors in whole grain health is processing. The more a grain is broken down, the faster it is digested and absorbed. Finely ground whole wheat flour, for example, raises blood sugar far more rapidly than intact wheat berries or steel-cut oats, even though both technically contain the same components.

This matters because repeated blood sugar spikes increase insulin demand and can worsen insulin resistance over time, particularly in sedentary individuals or those under chronic stress. Research shows that the physical form of carbohydrates strongly influences post-meal glucose and insulin responses, independent of fiber content alone (Jenkins et al., 2002).

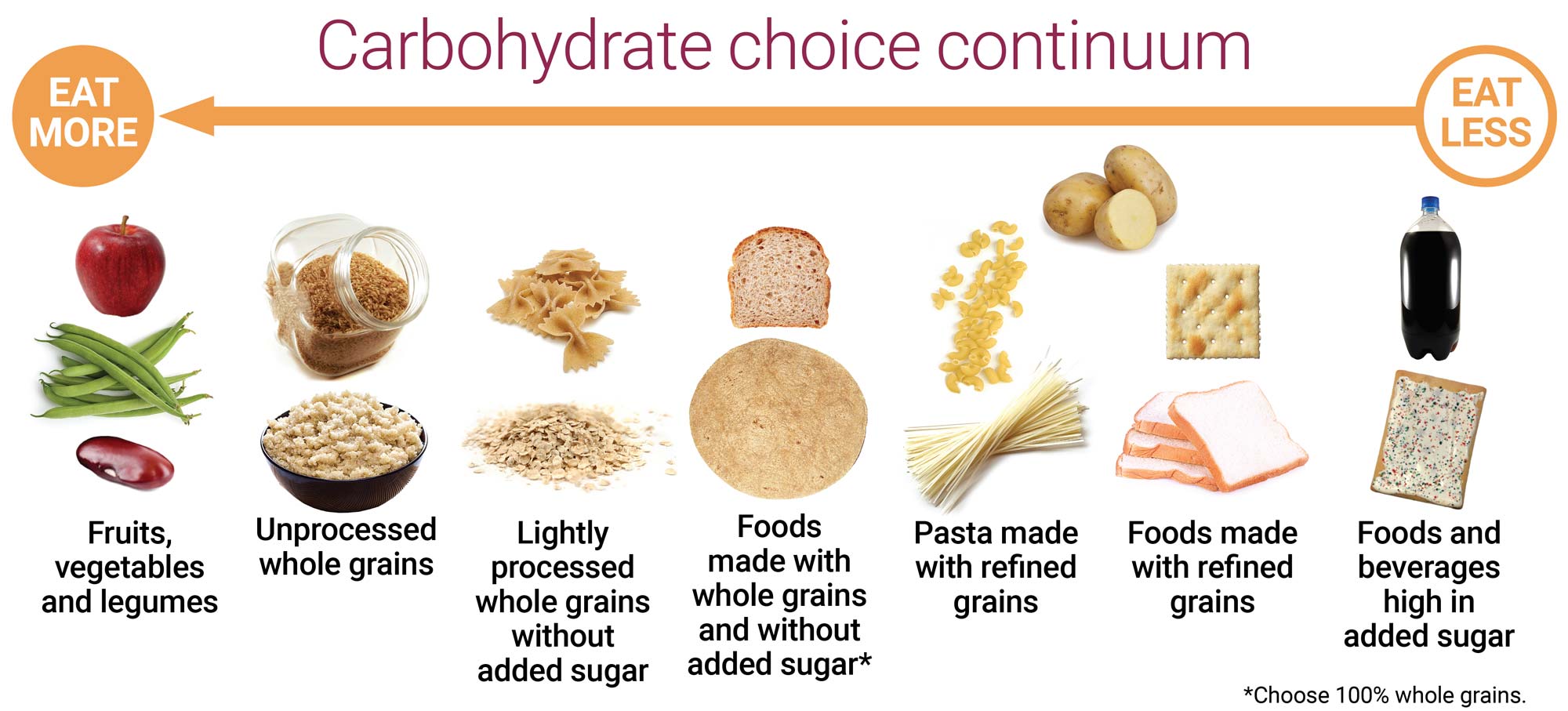

In practical terms, intact grains such as oats, barley, quinoa, and rice behave very differently from breads, cereals, and crackers made from whole grain flour. Structure matters as much as ingredients.

Fiber Type Matters More Than Fiber Amount

Not all fiber works the same way. Whole grains are often praised for their fiber content, but the type of fiber determines how beneficial that fiber will be. Viscous and fermentable fibers, such as beta-glucans found in oats and barley, slow gastric emptying, stabilize blood sugar, and feed beneficial gut bacteria. These fibers are strongly associated with improved cholesterol levels and metabolic health.

In contrast, bran-heavy fibers that are poorly fermentable may add bulk but offer fewer metabolic benefits. Simply adding bran back into refined flour does not recreate the physiological effects of an intact grain. This distinction explains why some “high-fiber” whole grain products fail to deliver the benefits consumers expect.

The Hidden Issue: Mineral Absorption and Phytates

Whole grains naturally contain phytates, compounds that bind to minerals such as iron, zinc, calcium, and magnesium, reducing their absorption. This does not make whole grains inherently harmful, but it does mean they should not dominate the diet, especially during periods of high stress, heavy training, or increased nutritional demand.

Diets that rely heavily on grains as a primary calorie source, without sufficient variety, can contribute to subtle mineral deficiencies over time. Rotating carbohydrate sources and pairing grains with mineral-rich foods helps mitigate this effect. Traditional preparation methods such as soaking, fermenting, or sprouting grains also reduce phytate content and improve mineral bioavailability (Lopez et al., 2001).

Timing Matters: When You Eat Grains Changes the Outcome

The body handles carbohydrates differently depending on the time of day and activity level. Insulin sensitivity is generally higher earlier in the day and after physical activity. Eating whole grains during these windows allows glucose to be used more efficiently for energy and recovery rather than stored as fat.

Studies show that carbohydrate tolerance improves following exercise, making post-training meals an ideal time to include grains without negative metabolic effects (Ivy, 2004). In contrast, large grain-heavy meals late at night, especially when paired with stress or sleep deprivation, are more likely to disrupt blood sugar regulation.

How to Eat Whole Grains More Intelligently

Rather than asking “Is this whole grain?” a better question is “How does this grain behave in my body?” Practical guidelines include prioritizing intact grains over flours, pairing grains with protein or fat to slow digestion, rotating carbohydrate sources rather than relying on grains daily, and aligning grain intake with periods of higher insulin sensitivity.

Whole grains are not automatically good or bad. Their impact depends on quality, processing, timing, and individual physiology. When eaten thoughtfully, they can support energy, gut health, and long-term metabolic stability. When relied on blindly, they can quietly undermine those same goals.

The Bottom Line

Whole grains are a tool, not a guarantee. The label alone does not determine whether a grain will support your health. Structure, fiber type, mineral balance, timing, and personal context all shape the outcome. Choosing intact grains, eating them at the right time, and avoiding over-reliance allows whole grains to work with your physiology rather than against it.

Smart nutrition isn’t about rules. It’s about understanding how foods behave once they’re inside the body.

References

Aune, D., Keum, N., Giovannucci, E., Fadnes, L. T., Boffetta, P., Greenwood, D. C., … Norat, T. (2016). Whole grain consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all cause and cause specific mortality: Systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ, 353, i2716. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i2716

Ivy, J. L. (2004). Regulation of muscle glycogen repletion, muscle protein synthesis and repair following exercise. Journal of Sports Science & Medicine, 3(3), 131–138.

Jenkins, D. J. A., Kendall, C. W. C., Augustin, L. S. A., Franceschi, S., Hamidi, M., Marchie, A., … Axelsen, M. (2002). Glycemic index: Overview of implications in health and disease. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 76(1), 266S–273S.

Lopez, H. W., Leenhardt, F., Coudray, C., & Remesy, C. (2001). Minerals and phytic acid interactions: Is it a real problem for human nutrition? International Journal of Food Science & Technology, 36(7), 727–739.