Eye Strain Explained: Causes and Simple Fixes

Eye strain has become so common that many people treat it as background noise. Tired eyes, dull headaches, slower thinking, or a vague sense of brain fog after a long day on screens are often dismissed as normal. Eye strain is frequently blamed on weak eyesight or aging. In reality, it is rarely an eye problem alone. It is a nervous system and workload problem.

The visual system was designed for movement. It evolved to scan horizons, shift focus, and track objects in space. Modern work demands the opposite. It asks the eyes to lock into a fixed distance, reduce blinking, and process dense visual information for hours at a time. Over time, this mismatch creates strain not just in the eyes, but in the brain systems responsible for interpreting visual input.

Understanding eye strain is not about finding the perfect exercise or special glasses. It is about recognizing what the visual system responds to and removing unnecessary load.

What Actually Causes Eye Strain

Screen time is often blamed, but duration alone is not the root issue. The primary drivers of eye strain are how the eyes are used during that time.

Sustained Near Focus

When staring at a screen, the ciliary muscles that control lens shape remain contracted to maintain near focus. These muscles are not designed for prolonged static holds. Extended contraction reduces flexibility and increases perceived effort, leading to discomfort and fatigue (Rosenfield, 2016).

Reduced Blink Rate

During concentrated visual tasks, blink frequency can drop significantly. Blinking spreads the tear film across the eye’s surface and maintains optical clarity. When blinking decreases, the tear film becomes unstable, increasing dryness and visual noise that the brain must compensate for (Portello et al., 2013).

Limited Eye Movement Variety

Natural vision involves constant micro movements including horizontal scanning, vertical shifts, and changes in depth. Screen use narrows this range. When movement patterns are restricted, certain eye muscles become overused while others disengage, contributing to muscular imbalance and strain.

Increased Cognitive Load

Eye strain is not purely mechanical. When visual input becomes less clear or more effortful, the brain increases processing demand to interpret it. This added effort is often experienced as mental fatigue, reduced focus, or headaches rather than eye pain alone (Sheedy et al., 2003).

Eye strain emerges when the visual system is forced into static, repetitive, low variation work that it was never optimized to handle.

Why the Brain Feels Tired When the Eyes Are Overworked

Vision is an active process. A large portion of the brain’s cortex is involved in visual processing. When the eyes struggle due to dryness, sustained focus, or muscular tension, the brain compensates.

This compensation often presents as slower information processing, difficulty sustaining attention, increased light sensitivity, and headaches or pressure around the eyes.

The brain interprets visual inefficiency as increased task difficulty. Over time, this elevates perceived effort and contributes to what many people describe as screen fatigue or brain fog (Agarwal & Goel, 2020).

Relief does not come from forcing the eyes to work harder. It comes from restoring visual efficiency and reducing unnecessary demand.

What Actually Fixes Eye Strain

Eye strain is not resolved by strengthening the eyes or pushing through discomfort. Effective fixes remove constraints and restore natural function.

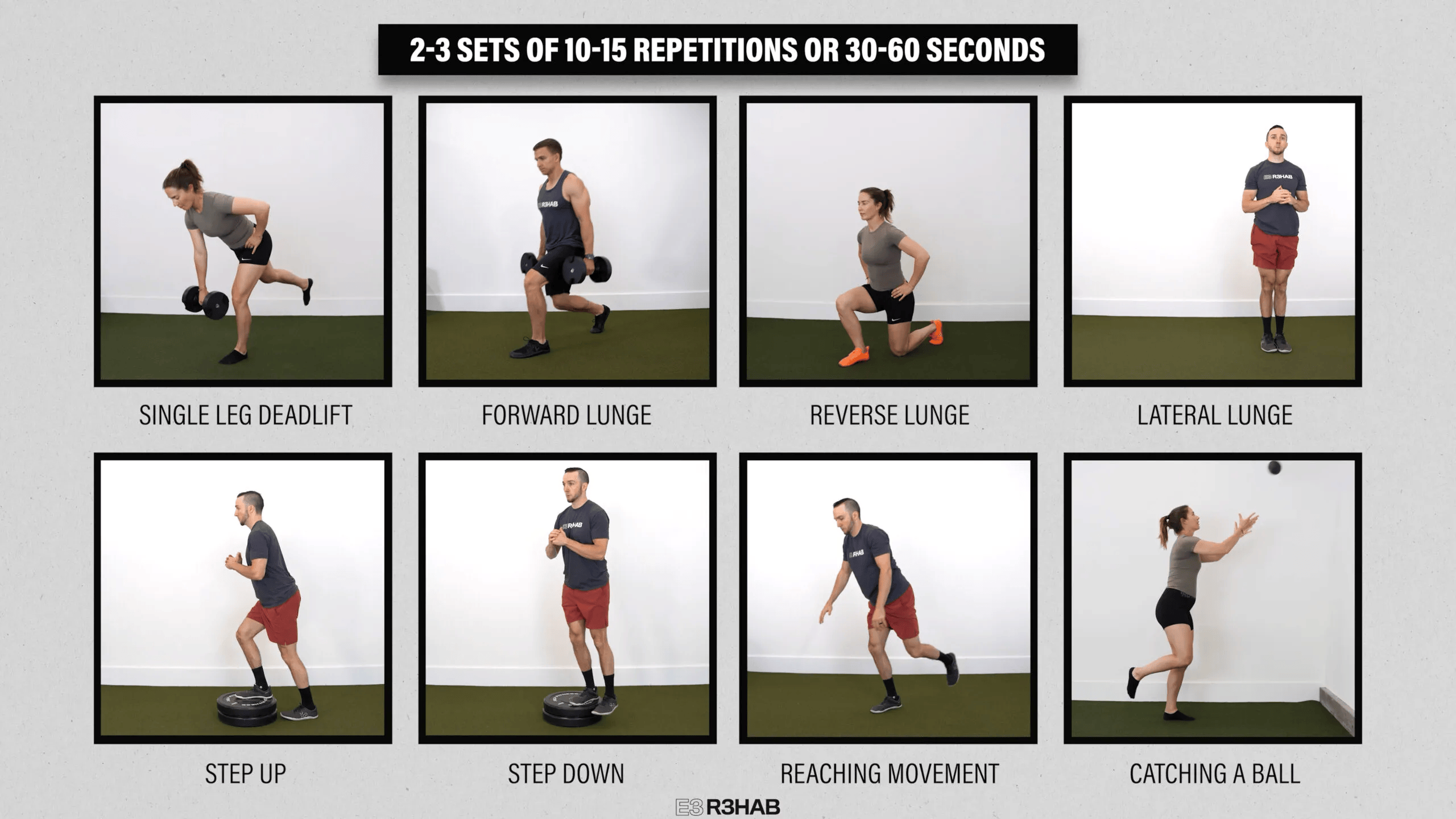

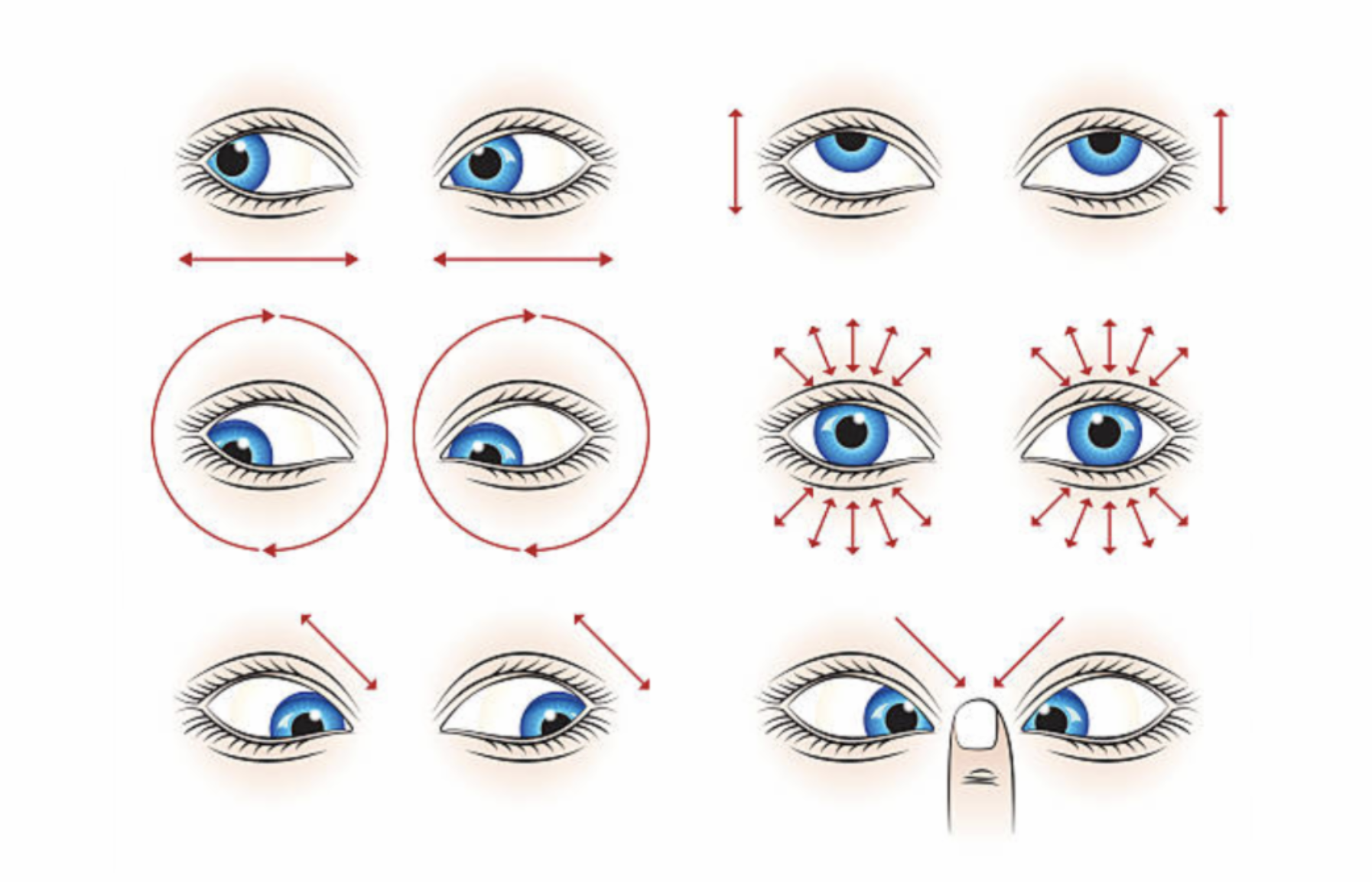

Movement Variety

Side to side, up and down, and circular eye movements redistribute muscular load and prevent repetitive overuse. Variety matters more than intensity. Gentle motion allows tension to dissipate.

Focus Flexibility

Alternating between near and far targets relaxes sustained ciliary muscle contraction. This shift reduces accommodative stress and improves focus adaptability, which is one of the most reliable ways to reduce discomfort during prolonged visual tasks (Rosenfield, 2016).

Gentle Execution

Eye exercises should feel calming rather than effortful. Straining to perform them correctly defeats the purpose. Relief comes from lowering neural demand, not increasing it. If an exercise feels tiring, it is likely adding load rather than removing it.

These strategies work because they remove unnatural constraints imposed by modern visual habits.

A Smarter Way to Think About Eye Exercises

There is no single ideal routine. The name of the exercise does not matter. What matters is whether it restores what prolonged screen use removes.

Ask three simple questions.

Does this introduce movement where there has been stillness

Does it allow the eyes to change focus distance

Does it reduce effort rather than demand performance

If the answer is yes, it is likely helping.

Actionable Insights

Short movement breaks

Every 30 to 60 minutes, spend one to two minutes moving the eyes in multiple directions without forcing range.

Near far shifts

Alternate focus between a close object and a distant point for 30 to 60 seconds to release accommodative tension.

Blink resets

Practice slow, intentional blinking during periods of intense focus to stabilize the tear film and reduce visual noise.

These interventions are small but effective because they align with how the visual system is built to function.

Vision as a System Problem

From a systems perspective, eye strain is feedback. It signals that visual environment and task demands are misaligned with human physiology. Screens themselves are not inherently harmful. Static, high demand, low variation visual work is.

The goal is not to eliminate screens or chase perfect ergonomics. The goal is to reintroduce movement, variability, and rest into the visual system so the brain does not have to work overtime just to see clearly.

The Takeaway

Eye strain is not a weakness and it is not inevitable. It is the predictable result of forcing a dynamic biological system into static conditions for too long. The fix is not more discipline or stronger eyes. It is smarter load management.

Restore movement. Restore focus flexibility. Reduce unnecessary effort.

When the eyes move freely and see clearly, the brain follows.

References

Agarwal, S., & Goel, D. (2020). Computer vision syndrome: A review of ocular causes and potential treatments. Ophthalmic & Physiological Optics, 40(3), 335 to 345. https://doi.org/10.1111/opo.12680

Portello, J. K., Rosenfield, M., Chu, C. A., & Chen, J. (2013). Blink rate, incomplete blinks and computer vision syndrome. Optometry and Vision Science, 90(5), 482 to 487. https://doi.org/10.1097/OPX.0b013e31828f09a7

Rosenfield, M. (2016). Computer vision syndrome: A review of ocular causes and potential treatments. Ophthalmic & Physiological Optics, 36(5), 502 to 515. https://doi.org/10.1111/opo.12306

Sheedy, J. E., Hayes, J., & Engle, J. (2003). Is all asthenopia the same? Optometry and Vision Science, 80(11), 732 to 739. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006324-200311000-00008