Why Balance Training Is Secretly Brain Training

When most people think about “training your brain,” they imagine meditation, puzzles, reading, or learning a new skill. Balance training rarely makes the list. It feels too simple, too physical, too basic. Like something you do in a warm up, or something older adults do to prevent falls.

But balance training is one of the most direct ways to train your brain through your body.

Because balance is not a muscle skill. It’s a nervous system skill.

Your ability to stay steady, react quickly, and control your body in unpredictable situations depends on how well your brain can process information, make decisions, and send clean signals to your muscles. The better that system works, the more stable you are. Not just on one leg in a gym, but in real life when you slip, pivot, step off a curb, or move fast without thinking.

If you want to move better, feel more athletic, and protect your body long term, balance training is one of the highest return habits you can build.

Balance is a full time conversation between your brain and your body

Balance looks like a physical ability, but it’s actually your brain constantly running calculations in the background.

Every second you’re upright, your nervous system is doing three major jobs:

First, it’s collecting information from your senses. Your eyes tell you where you are in space. Your inner ear tells you if your head is moving or tilting. Your joints and muscles send feedback about position, pressure, and tension. That internal sensing system is called proprioception, and it’s a huge part of how you move without needing to look at your body (Shumway Cook and Woollacott 2017).

Second, your brain has to interpret that information and decide what matters. Are you stable? Are you drifting? Is the ground uneven? Did your weight shift too far forward? This is not slow thinking. It’s instant processing.

Third, your brain sends rapid corrections to keep you upright. Small adjustments happen through your ankles, hips, and core before you even notice them. When balance is good, these corrections are smooth and efficient. When balance is poor, the corrections are delayed, exaggerated, or messy, which is when you wobble, trip, or feel unstable.

So every time you train balance, you’re not just strengthening muscles. You’re improving the speed and quality of that brain body feedback loop.

Balance is one of the fastest ways to upgrade coordination

A lot of people feel “uncoordinated” and assume it’s just who they are. But coordination is trainable, and balance training is one of the simplest entry points.

When you practice balancing, your brain is forced to get more precise. It has to recruit the right muscles at the right time, with the right amount of force, while filtering out unnecessary tension.

This matters because many injuries and movement problems aren’t caused by weakness. They’re caused by poor timing.

For example, you can have strong legs and still roll your ankle. You can have a strong core and still feel unstable when you change direction. You can lift heavy in the gym but still feel awkward during sports or fast movement.

Balance training improves the quality of your movement software, not just your movement hardware.

Your brain learns balance by making mistakes

This is the part people don’t expect.

Balance improves through error.

When you wobble, your nervous system gets a signal that your body is off center. Your brain learns where the edge is, how to correct it, and how to predict it next time. This is motor learning, and it’s how your brain refines movement patterns over time (Taube, Gruber and Gollhofer 2008).

That’s why balance training works best when it’s slightly challenging. Not impossible, not scary, but not comfortable either.

If you’re perfectly stable, your brain has nothing new to learn.

If you’re slightly unstable, your brain adapts.

This is also why balance training can feel mentally tiring even when it looks “easy.” Your brain is doing active problem solving. It’s updating your internal map of your body.

Balance training sharpens reaction time in real life

Most people don’t get injured doing slow controlled movements. They get injured when something unexpected happens.

A slippery floor. A sudden pivot. A missed step. A quick change of direction. A dog running into your legs. A crowded train stopping abruptly.

In those moments, your body needs fast reflexive stability.

Balance training improves your ability to recover quickly because it strengthens your postural control system. This includes the reflexes and automatic adjustments that protect your joints when you’re thrown off balance.

Research shows that balance training can improve neuromuscular control and stability, which is one reason it’s used in injury prevention programs, especially for ankles and knees (Taube, Gruber and Gollhofer 2008).

You’re not just learning to stand still. You’re training your body to save you when things go wrong.

It’s also a cognitive workout, just disguised as movement

Here’s the “brain training” part most people miss.

Balance demands attention, focus, and sensory integration. You have to monitor your body, adjust your position, and respond to tiny changes without overcorrecting. That is a cognitive task.

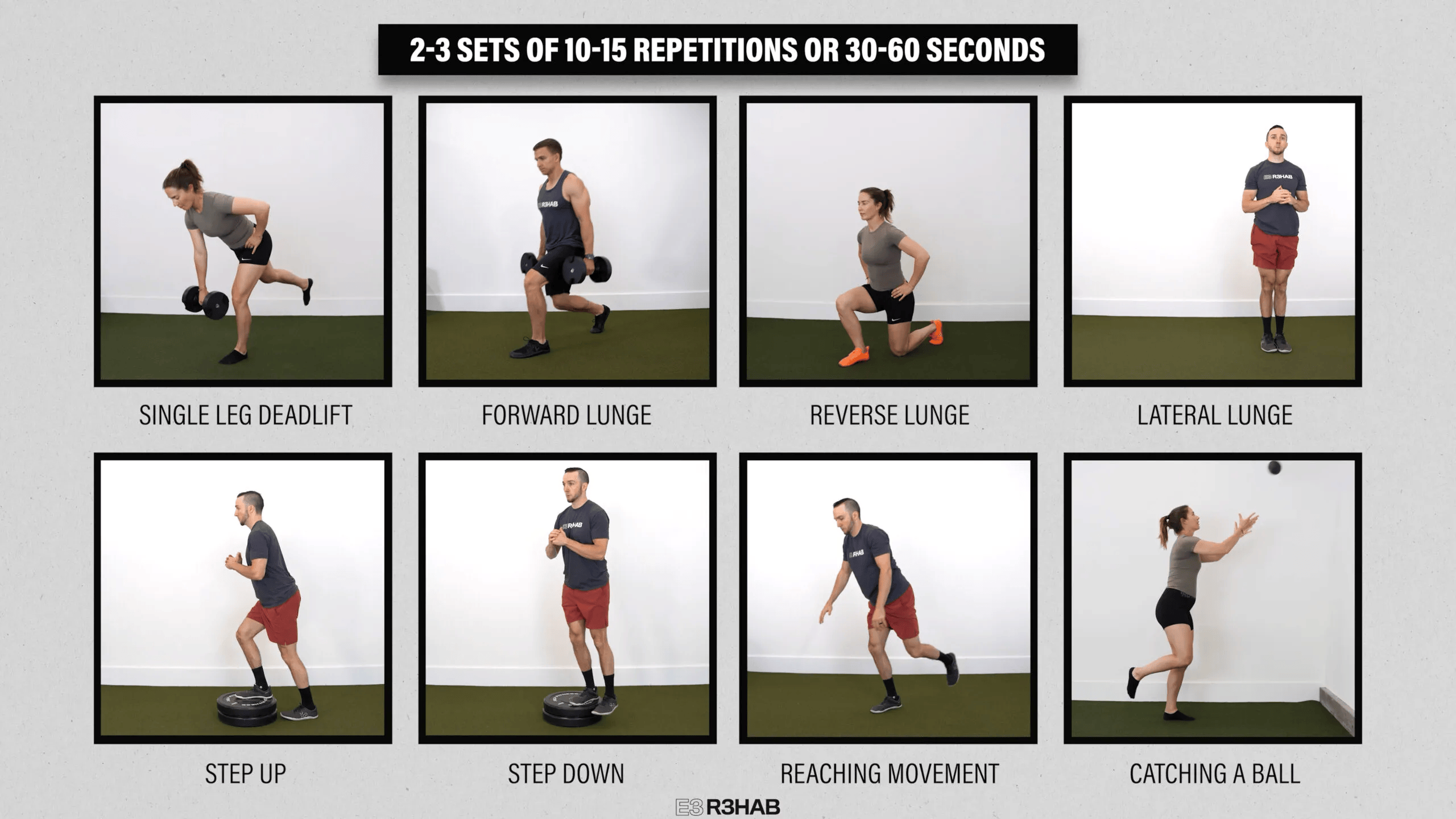

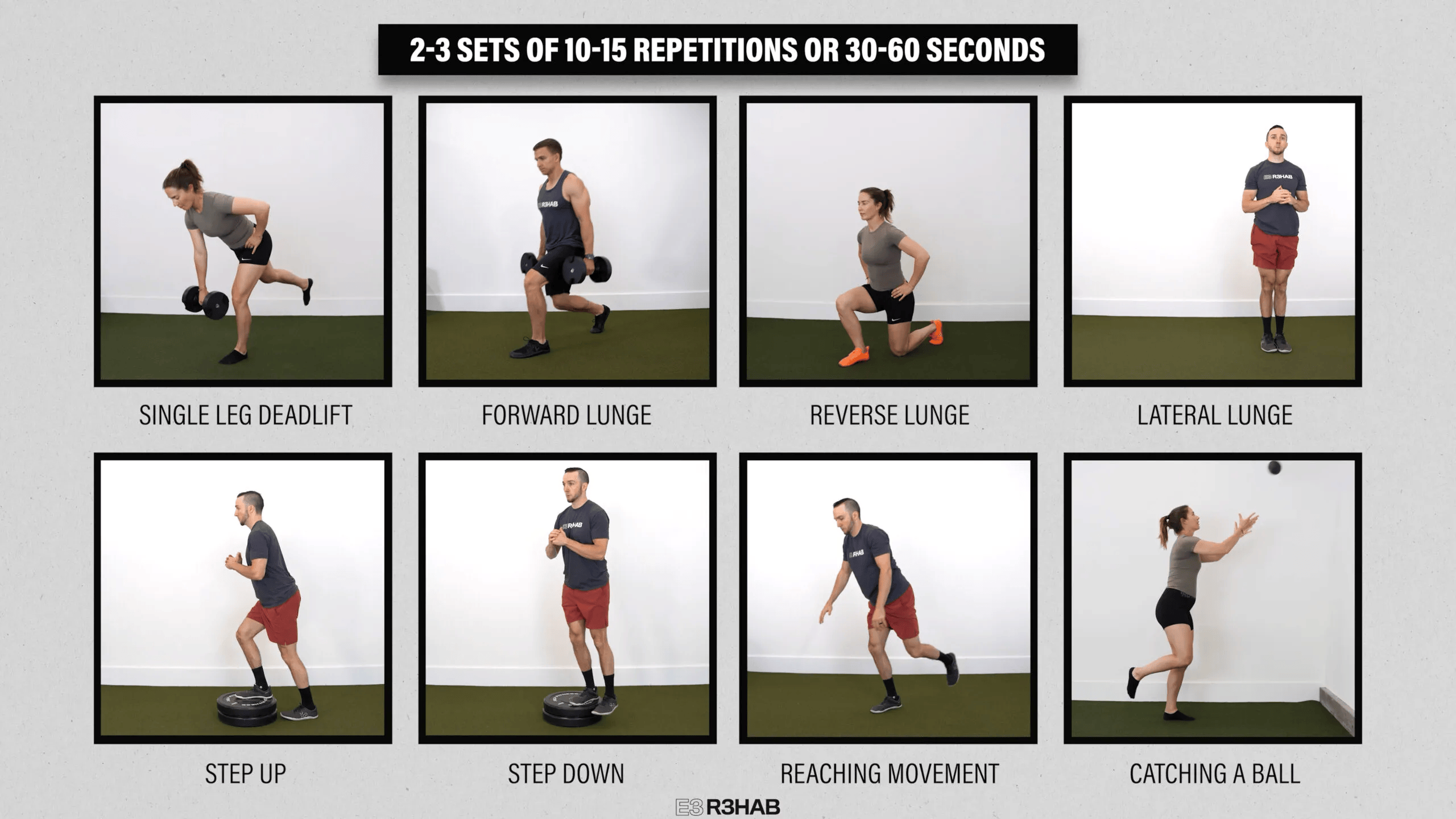

Balance gets even more brain heavy when you add complexity, like:

Turning your head while balancing

Closing your eyes

Balancing on an unstable surface

Catching and throwing a ball

Balancing while doing a mental task

In research, this is often called dual task training, where balance and cognitive load compete for attention. This matters because real life is always dual task. You walk while thinking. You step off a curb while checking directions. You move through crowds while talking. Balance training that challenges attention can improve how well you stay stable under distraction (Shumway Cook and Woollacott 2017).

That’s why people often feel more “switched on” after balance work. It wakes up the system.

Balance training is anti aging in the most practical way

If you care about longevity, balance training should be non negotiable.

Not because it looks cool, but because falls are one of the biggest threats to healthy aging. Balance, strength, and reaction time are protective factors that help people stay independent.

Balance tends to decline if you don’t use it. Modern life removes many natural balance challenges. We sit more, walk on flat surfaces, wear supportive shoes, and avoid unstable terrain. Your nervous system becomes less practiced at handling instability.

The good news is that balance responds quickly to training. Even small doses can make a difference, especially when done consistently.

In older adults, balance training is commonly recommended because it improves postural control and reduces fall risk, but the benefits apply to everyone. The earlier you build it, the more resilient you stay.

Balance training makes your strength usable

This is a key point if you already lift weights.

Strength is only as useful as your ability to apply it.

If you can deadlift heavy but you lose balance during a quick lunge, your strength isn’t translating to real world movement. Balance training helps you express strength with control. It improves joint stability, body awareness, and alignment under load.

It also exposes weak links you might not notice in traditional training. A small wobble in the ankle. A hip that collapses inward. A foot that can’t grip the floor. A core that can’t resist rotation.

Balance training doesn’t just build stability. It reveals it.

And once you can see it, you can fix it.

The takeaway

Balance training looks like a physical skill, but it’s secretly a nervous system upgrade. It improves how your brain processes movement, reacts to instability, and controls your body under pressure. It sharpens coordination, improves reflexive stability, and makes your strength more usable in real life.

If you want to move with more confidence, protect your joints, and feel more athletic without adding more time to your workouts, balance training is one of the simplest habits with the biggest payoff.

You’re not just training to stand on one leg.

You’re training your brain to control your body.

References

Shumway Cook, A and Woollacott, MH 2017, Motor Control: Translating Research into Clinical Practice, 5th edn, Wolters Kluwer, Philadelphia.

Taube, W, Gruber, M and Gollhofer, A 2008, ‘Spinal and supraspinal adaptations associated with balance training and their functional relevance’, Acta Physiologica, vol. 193, no. 2, pp. 101–116, viewed 21 January 2026, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-1716.2008.01850.x.

Horak, FB 2006, ‘Postural orientation and equilibrium: what do we need to know about neural control of balance to prevent falls?’, Age and Ageing, vol. 35, suppl. 2, pp. ii7–ii11, viewed 21 January 2026, https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afl077.