Fascia Squats: A Hidden Key to Mobility for Seniors

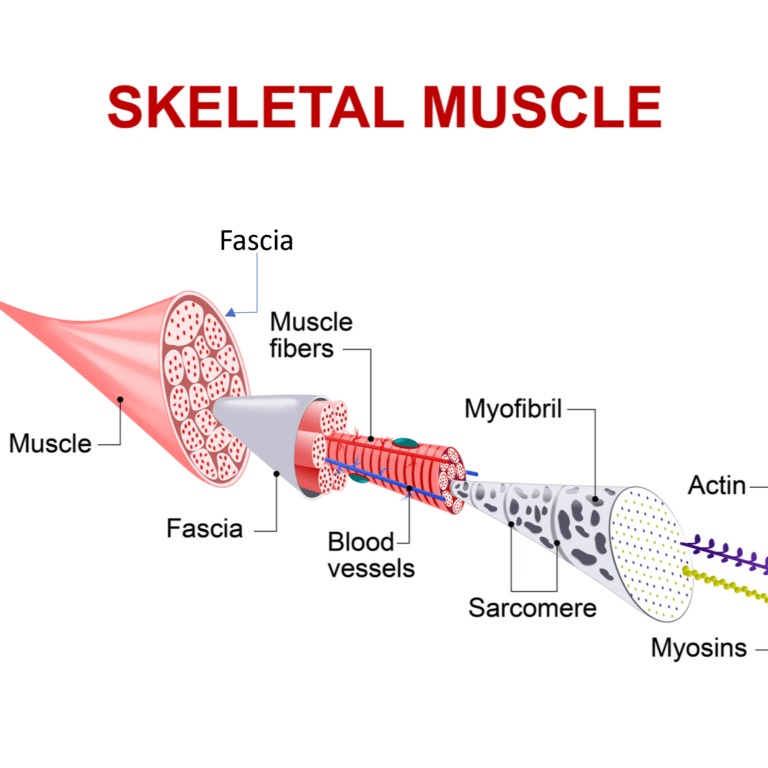

Mobility tends to decline with age, and most people assume this is simply because muscles weaken over time. While that is partly true, research shows that another factor plays an equally important role. The body’s fascia, a thin web of connective tissue that surrounds and links muscles and joints, gradually becomes stiffer with age. This stiffening reduces elasticity, limits range of motion, and makes daily activities such as bending, standing up, or climbing stairs more difficult.

Fascia squats are a gentle form of squatting that focus less on building strength and more on restoring flexibility and hydration to these connective tissues. By moving slowly, breathing with intention, and paying attention to smooth motion, seniors can use fascia squats to reduce stiffness, improve balance, and preserve independence. Unlike heavy strength training, this approach emphasizes fluidity, encouraging fascia to become more supple and resilient.

Why Fascia Squats Matter for Seniors

Healthy fascia allow muscles and joints to glide against each other with ease. When this tissue becomes dry or rigid, the body loses its natural spring and movements begin to feel heavy or restricted. Fascia squats work by gently compressing and stretching the connective tissue, which helps to push out old fluid and draw in new hydration. This process keeps the tissue moist and flexible, allowing joints to move more freely.

At the same time, these movements encourage the joints of the hips, knees, and ankles to move through their natural range. This improves lubrication in the joint spaces, making them less prone to stiffness and discomfort. Over time, fascia training also enhances the ability of the tissue to store and release elastic energy, which helps the body to move with more ease and less effort. For seniors, this means smoother walking, better stability, and a lower risk of falls.

The Benefits of Regular Practice

Practicing fascia squats regularly can help restore mobility that is often lost with age. Seniors who include them in daily routines may find that ordinary tasks such as getting in and out of a chair or bending to pick something up feel easier and less tiring. Consistent movement keeps fascia hydrated, reducing the tight and achy feeling that often comes after long periods of sitting. Balance and coordination also improve, which is critical for preventing falls. Beyond physical benefits, regaining comfort in movement can provide a sense of confidence and independence, improving overall quality of life.

How to Get Started

Fascia squats do not require any equipment and can be practiced almost anywhere. For safety, beginners can use a chair, wall, or countertop for support until they feel stable. The goal is not to squat as low as possible but to focus on smooth and controlled movement. Even shallow squats are effective for hydrating fascia and nourishing the joints. Breathing steadily with each repetition helps maintain a relaxed pace. A few minutes of daily practice is far more effective for connective tissue than occasional longer workouts.

The Takeaway

Aging does not have to mean losing mobility. While muscle strength is important, fascia play an equally vital role in how the body moves. Fascia squats offer a simple and sustainable way for seniors to keep this hidden tissue healthy. By restoring hydration, improving elasticity, and enhancing stability, they can reduce stiffness and make everyday movement easier. With consistent practice, fascia squats may help older adults maintain independence, protect against falls, and continue enjoying the freedom of movement well into later years.

References

Huijing PA (2009) ‘Muscle as a collagen fiber reinforced composite: a review of force transmission in muscle and whole limb’, Journal of Biomechanics, 42(9):1189–1198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.04.001

Schleip R and Müller DG (2013) ‘Training principles for fascial connective tissues: scientific foundation and suggested practical applications’, Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 17(1):103–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbmt.2012.06.007

Wilke J, Krause F, Vogt L et al. (2017) ‘What is evidence-based about myofascial chains: a systematic review’, Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 98(3):454–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2016.07.023